The update lifecycle in aiogram

This article describes the key aspects of how Telegram bots work and will be useful for both beginners who are just starting out and for advanced developers. Specifically, we're talking about the aiogram framework, but all the ideas presented can be seen anywhere. I assure you that after reading this, it will be much easier for you to understand all the details of the mechanism as a single process

Article Contents

- The concept of an update in Telegram

- Methods of receiving updates

- Processing of updates

- Router and dispatcher

- Middleware

- Filter

- Handler

Local terms All terms should be understood in the context of Telegram and aiogram. Similar concepts can be found in many places, so don't take them as universal definitions for everything!

Update

💡 An Update — is an object with data that appears as a result of a certain action from the client's side, for example, a user or a bot

Examples for better understanding

- A user writes a message to the bot — an update is created with all the data by which we understand where, when, and how the message was sent, so it can be processed

- A user joins/leaves a channel or group — a corresponding update appears. Which chat it was, the user's updated status in the chat...

- An admin bans someone — we see an update with data about this event: in which chat, whom, for how long, and so on

- A user presses a button — we receive an update with data about the button

Why don't bots see each other's messages? A trivial but simple example. Imagine there are two bots in a group. The first one sends the message «chicken», the second one replies «egg». It seems normal, but what if you configure the first bot to reply to «egg» with «chicken» again? Then you get an infinite loop of messages chicken, egg, chicken, egg... This is why Telegram has such a restriction

The term update should be used as a general concept that speaks about some events and their processing. A good sentence would be: «My bot doesn't catch updates» – this literally means that the bot does not react to the user's actions in any way

Types of updates

An update should be understood as some event. In turn, each event that has occurred has a defined update type. This is done so that one can easily understand the type of event (new message, user deletion, button click, etc) and standardize the data that will be included in the update. Because it is better to have a certain type of update with predefined fields that can be in it, rather than receiving a universal update and trying to figure out what happened

The most commonly used update types

- Message – contains data about a message in a chat: text/media, formatting, sender data, possibly a keyboard, and much more

- CallbackQuery – is responsible for inline buttons, it contains data that was put into the buttons during their creation, user data, chat data, and more

- InlineQuery – comes in inline mode (eg bots like @gif receive them), contains the user's query, chat type, and other data for managing the output results

- ChatMemberUpdated – stores data about updates of users/bots in a chat, joining/leaving the chat, changing permissions, and so on

- ChatJoinRequest – represents a request to join a chat with the corresponding data

Methods of receiving updates

You can manage a bot without running it It is often said «send from under the token» – that is, take the bot's token and send the necessary request to the Telegram Bot API. To do this, you don't need to run the update receiving mechanism, but its operation will not interfere in any way

- 🔄 Polling — a polling mechanism and the simplest way to get updates. The client (that is, our bot on the server) constantly, at small intervals, sends requests to api.telegram.org to get new updates. This mechanism is very easy to try manually, you can send the corresponding request directly in your browser and see the response from Telegram (

https://api.telegram.org/botTOKEN/getUpdates, whereTOKENis your bot's token) - ⏳ Long-polling — a cooler version of polling. The bot again sends requests to api.telegram.org, but not constantly. If there are no new updates, Telegram maintains a connection with the bot's server until new updates appear. When updates appear, Telegram sends the updates to the bot over the previously opened connection. This is some kind of hybrid of polling + an idea from webhook

- 🌐 Webhook — a method of receiving updates in which we do not need to poll the API at all. The key point is to inform Telegram where we want it to send us updates. Thus, our bot just waits for new events. However, this method of receiving updates requires additional configuration

Which update receiving mechanism should be chosen? Long-polling or Webhook — that is the question. To answer it, one should analyze the load on the bot, the need for its scaling. If in the future the bot will be popular only locally, then polling will be enough. A webhook will make sense, for example, for organizing a high-load platform or for a quality multibot. But the method of receiving updates can always be changed!

Processing of updates

The full path of update processing includes the following stages

- The server with the bot receives an update

- The bot eats the update (feed methods, which pass the update directly to the bot)

Then the update goes through the so-called chain of processors

- Passing through outer middlewares

- The update running through the hierarchy of routers

- Filters for the update (custom and built-in)

- It gets into inner middlewares

- Event processing in a handler

- Post-processing

Knowledge vs. trial and error Not every person who uses aiogram understands how an update passes through all these objects. It is important to be able to see the big picture. Then you will be able to quickly understand where and how to implement this or that bot logic!

Router and dispatcher

We received an update, what's next? Obviously, the bot should respond to some things and not to others — that is, filter the events that are relevant to it. Here, registrations and processors come into play — they are the foundation of the entire filtering system

- 📌 Registration can be understood as setting a processor for the specified update type in a certain order (priority) relative to other processors

- 🌀 Processors can be handlers, filters, and middlewares that somehow interact with the update (more on each of them a little later). The point is that when aiogram receives an update, it will try to «catch it with processors», and in the order of their registration. First, the framework will try to give the update to those processors that were registered earlier, and only then (if it did not fit any of them) to others

Registrations are important One of the most common mistakes among beginners is precisely the misunderstanding of the nature of registrations. Keep this in mind — and you will have fewer thoughts about why this update first goes there and not here

Now let's move on to the organization of catching updates, namely to routers. Perhaps you have only used aiogram 2.X and routers scare you, it's not clear why they are needed. Then I will try to change your mind!

- 📡 Router — is an object that represents a branch of registered processors, it can also have a name

- 🎩 Dispatcher — the root (main) router that contains all the nested routers of the bot, stores the storage and FSM strategy, and is responsible for starting the bot (or feeding it updates). You can also register processors with it

Purely theoretically, one dispatcher as a router would be enough to handle all events. But using routers has its advantages

Modularity:

- Each router is responsible for a specific functionality of the bot

- This improves code organization and makes it more structured

- Examples:

- The

adminrouter contains handlers only for administrators - The

userrouter processes commands from regular users - The

paymentrouter is responsible for all payment-related operations

- The

- This approach simplifies code navigation and maintenance

Registration:

- Instead of registering each processor in the dispatcher, you can manage entire branches of processors

- This makes it easier to set the priority of update processing

- Example:

- First, updates from the

userrouter are processed - Then, if the update is not processed, it goes to the

adminrouter

- First, updates from the

- Important: the order of registration of processors within each router also matters

Flexibility:

- You can easily enable or disable entire groups of functionality

- This is useful for:

- Testing new features without affecting the main code

- Implementing «red buttons» to quickly disable certain functions

- Creating multibots where different sets of functions can be enabled depending on the context

- Example: you can temporarily disable the

paymentrouter for maintenance without affecting other bot functions

Privacy:

- Each router can have its own filters and middlewares

- This allows:

- Setting access rights checks once for the entire set of handlers

- Logging actions within a specific functionality

- Examples:

- The

adminrouter can have a filter that checks for administrative rights for all its handlers - The

paymentrouter can log all financial transactions without affecting other parts of the bot

- The

Hierarchy:

- Routers can contain other routers, creating a tree-like structure

- This allows:

- Implementing complex update processing systems

- Creating flexible access rights systems

- Example:

- The main

userrouter can contain sub-routersbeginner,advanced,premium - Each sub-router has its own set of commands and functions available for the corresponding user level

- The main

None of these advantages exist with a single dispatcher But don't think badly of the dispatcher. It serves more general purposes. The text above is aimed at convincing you not to use only one dispatcher in your bot (unless, of course, it's a primitive functionality). P.S. Switch to aiogram 3.X

How an update propagates through routers, their filters, and handlers (middlewares are not shown)

Middleware

🔐 A Middleware — is an object that acts as an intermediary link between processors and works with an update at the level of its type [1]. It has two types of registration [2]. Its use comes down to calling or not calling the next processor in the chain in the right place (according to the bot's logic) [3]. Middleware provides the opportunity for pre, «inner», post, and outgoing processing of updates [4]. They can be implemented as classes or functions (the first option is more common)

[1] Middleware registration is only possible at the update type level, so the content of the internal data of the update does not play any role for it (but no one said that during processing, middleware cannot act as a filter for specific data in the update)

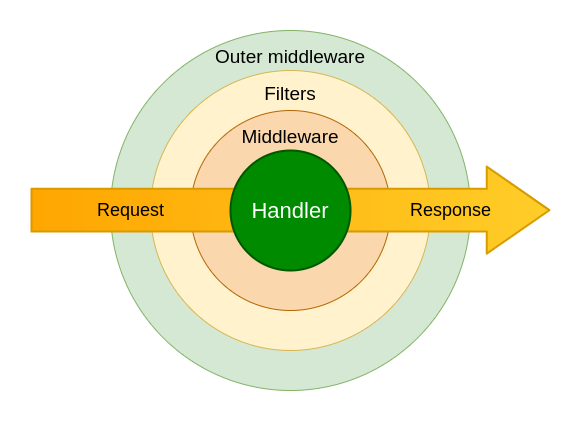

[2] Let's deal with the two types of registrations, for this, let's look at the figure below (original)

As you can see, there are outer middleware and middleware, in simple terms — outer and inner. It would be correct to think that they have different registration priorities for an update

What is the difference between these registrations?

- If there are 2 middlewares, one registered as outer, and the other as inner (for the same type), then a newly-arrived update will first meet the outer one, and only then the inner one

- The outer middleware will be called for every update with the registered type, which cannot be said for inner registration

- In the outer middleware, when processing an update, it is not known which handler it will potentially go to, that is, everything is at the update type level. But a middleware registered internally will have access to the update only after it has passed through all the previous processors, including filters. This will mean that the bot must have some specific handlers to react to this update

Registration for any update A middleware can be registered in such a way that any updates (of the update type) will come to it. The type of registration does not affect this in any way. Formally, outer and inner registration for the update type are different things, but in fact, they will work the same. P.S. It's better to use outer for this

[3] About calling the next processor in the chain. For example, let's look at this middleware code (original)

from aiogram import BaseMiddleware

from aiogram.types import Message

class CounterMiddleware(BaseMiddleware):

def __init__(self) -> None:

self.counter = 0

async def __call__(

self,

handler: Callable[[Message, Dict[str, Any]], Awaitable[Any]],

event: Message,

data: Dict[str, Any]

) -> Any:

self.counter += 1

data['counter'] = self.counter

return await handler(event, data)

Special attention should be paid to the await handler(event, data) call. This action passes the update further down the chain of processors. If there is a case in the middleware (for example, under certain conditions) where await handler(event, data) is not called, it will mean that the update is discarded/dropped. That is, none of the processors below will get access to the update as if it never existed. Therefore, we can say that in general, the job of a middleware is to pass data from the update somewhere and/or drop it under certain filtering conditions

[4] About the types of processing

- Pre-processing (outer registration) is useful in cases where a minimum of information is sufficient for some actions and they need to be done as early as possible

- «Inner» processing (author's name) occurs in inner middlewares. Knowing that the update has passed all the filters and is potentially going to a handler (where the bot reacts to a message from the user), it can be processed accordingly

- Post-processing involves some actions in the middleware after calling the next processor in the chain and can be present in both outer and inner registrations. This is useful if the processing in the middleware can be done after the update has completed its path down the chain of processors below. Thus, the update will not be delayed for an optional action that can be done after it has passed the entire chain

- Outgoing processing using middlewares is a slightly separate topic that not many people know about. The essence is to process the actions of the bot itself (the

BaseRequestMiddlewareclass)

Dependency Injection

In aiogram, the Dependency Injection mechanism allows processors to receive dependencies (data necessary for the call) from other objects that have them or received them in the same way before. These dependencies can be obtained in different ways depending on the type of processor:

- Middleware — receives dependencies through the

dataargument — a dictionary from which the required data can be extracted by key - Filters and handlers — dependencies are passed as optional keyword arguments. To access them, you need to specify the required keys directly in the function parameters

- Filters in handlers — can use

MagicDataor the.as()method to receive dependencies These different methods allow for flexible management of dependencies and ensure efficient access to data in different parts of the application

Delegator middleware

This is an author's name from the word delegate (to pass on), which describes middlewares that pass data to processors using Dependency Injection. Perhaps, the delegator middleware is mainly used to obtain a database session so that the processors below have a convenient interface for querying it. Also, data processed in a certain way that depends on the update can be passed (eg something filtered from the update data or data on the bot's side related to the user). To use this mechanism in the context of middlewares, you need to add data through the data argument. This is a dictionary whose data is passed to the processors below

Filter

🕸 A Filter — is probably the widest range of processors. However, they are divided into two main types: custom and out-of-the-box. Here we will discuss custom ones, and we will discuss the rest later. A filter can be:

- an asynchronous function

- a synchronous function

- an anonymous function

- any awaitable object

- a subclass of

aiogram.filters.base.Filter - an instance of

MagicFilter

When called, filters must return a boolean or a dictionary, which determines whether the update has passed the filtration (it only fails on False)

Unlike middleware, the task of a filter is simply to filter the update. But sometimes, the filtering logic can be more complex than a simple comparison. For example, it makes sense to write a custom filter if you need to check whether the update belongs to a group admin

An example of a simple filter that compares the message text with a given one (original)

from aiogram import Router

from aiogram.filters import Filter

from aiogram.types import Message

router = Router()

class MyFilter(Filter):

def __init__(self, my_text: str) -> None:

self.my_text = my_text

async def __call__(self, message: Message) -> bool:

return message.text == self.my_text

@router.message(MyFilter("hello"))

async def my_handler(message: Message):

...

Combinations of filters

If several filters are set during registration, logical AND will be used (the update must pass all of them). It is also allowed to have several registrations for one processor, in which case logical OR will be used (it is enough for the update to pass the filters of at least one registration). You can also use the magic filter syntax for combinations

Delegator filter

Yes, they can pass data using Dependency Injection. This is possible if the filter returns a dictionary. Then its data can be obtained in the following processors. This is very convenient for obtaining certain data from an update

Handler

🦾 A Handler — is a function registered to process updates. It is the final processor (the update goes no further) in which it is customary to interact with the user. The function should not return anything and can be registered both with and without filters. But at the same time, a handler can be implemented as a subclass

Ghost handler A common cause of errors for beginners is a handler without filters. All updates for which it is registered will go into such a handler. Therefore, if you understand that an update is going somewhere it shouldn't, remember if you have such a handler. In general, its use is not bad practice, you just need to work with it carefully

Not much can be said about the handler itself, but we can talk about the filters that work with it. We discussed custom filters above, now it's time for the built-in ones

Built-in filters for handlers

- Command – a convenient filter for catching commands, especially if you need to get the command arguments (eg get

123from the command/start 123) - ChatMemberUpdated – a flexible filter for updates about user updates in chats (eg you can filter only new users)

- Magic filters – lambda-like filters for comparing update data (as main filters, eg filtering text

F.text == "hello") - MagicData – allows you to compare update data with data passed through Dependency Injection

- Callback Data Factory – a filter construction tool that suggests using data embedded in an inline button

- Exceptions – filters for catching errors in processors

Found a mistake? Feedback: hello@shaonis.space